The iconic “jet d’eau” fountain in Switzerland’s second-biggest city Geneva.

Keystone

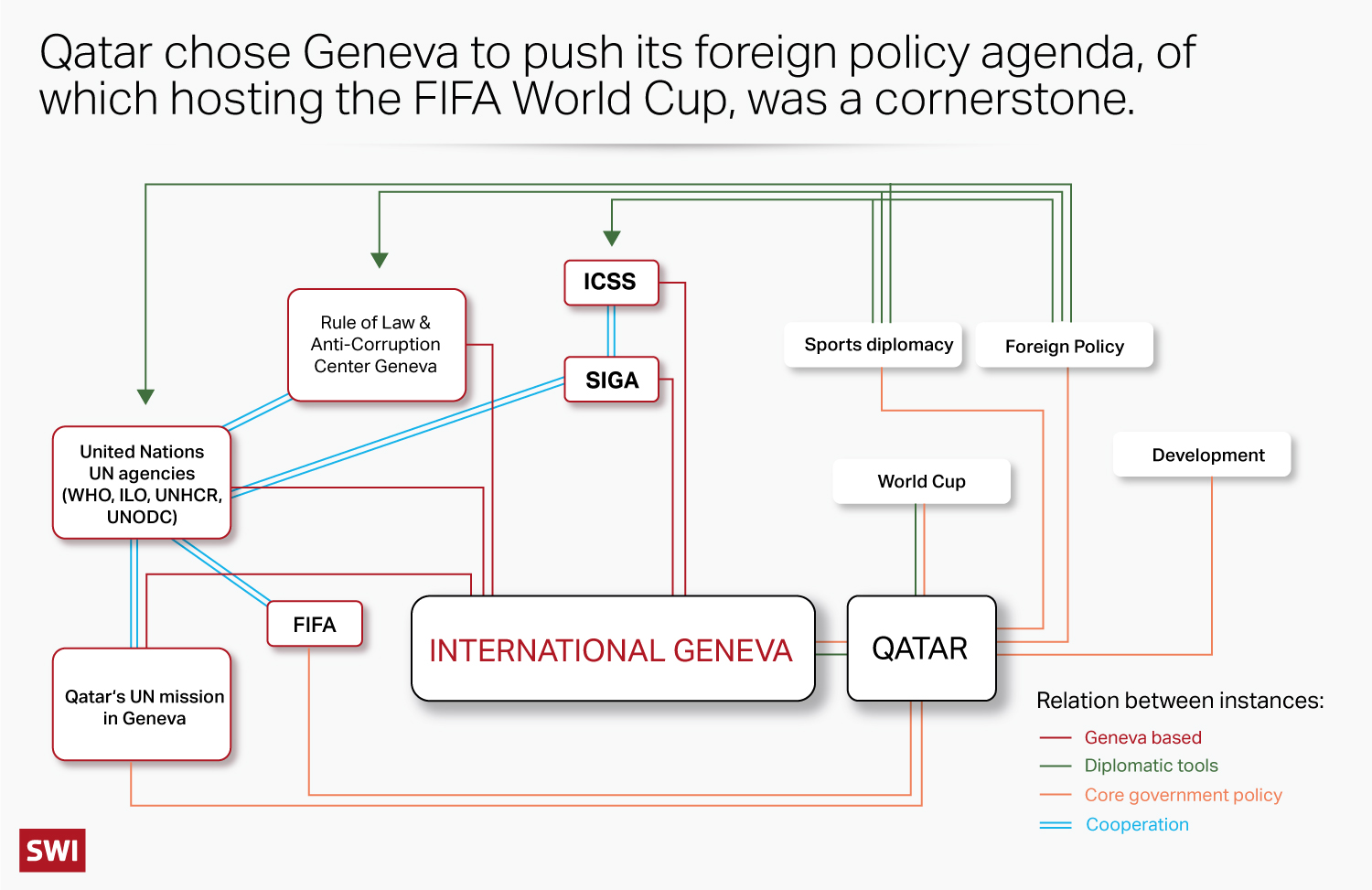

Located some 5000 km from the gravity-defying skyscrapers of the Qatari capital, Doha, Geneva has become as important to the emirate’s diplomacy as football has been to its global branding.

It is in Geneva that much of Qatar’s carefully-crafted global image-building has come to light. The city, known as a hub of international diplomatic activity, is not far from canton Vaud, home to many global sports associations and federations. And Zurich, where FIFA headquarters are located, is just a three-hour train ride away.

Qatar’s Geneva offensive

This is the first part of a three-part series about how Qatar has used Switzerland as a hub for efforts to boost its public image since being named host of the 2022 World Cup. In Part 2, we look at the International Centre for Sports Security (ICSS), while Part 3 reports on the Sports Integrity Global Alliance (SIGA) – two institutions which are Qatar-founded, Geneva-based, and faced with accusations of lacking transparency.

Geneva is also where the energy-rich state has established two initiatives – the International Centre for Sports Security (ICSS) and the Sports Integrity Global Alliance (SIGA) – directly and indirectly, to command a narrative around sports and transparency in the sector.

“It would be logical that Qatar is operating here,” says Marc Pieth, a Swiss anti-corruption expert. “Switzerland’s network of international organisations, sports organisations and diplomatic opportunities was 1722232129 being used by Qatar to create a positive image of itself globally”.

Sports diplomacy

Twelve years after winning the bid to host the football event, the Gulf state has seen sports diplomacy become an important element of its foreign policy as well as its development policy at home. All in all, the tiny state says it has spent at least $200 billion (CHF196 billion) on infrastructure ahead of the World Cup, plus hundreds of millions on top soccer champions, sponsored some of the best football teams in the world, and hosted a long list of global sporting events.

Qatar’s ambassador, Hind Bint Abdul Rahman Al-Muftah (second from left) to the United Nations in Geneva at a UNITAR signing event in Geneva.

Paula Dupraz-Dobias

“If Qatar succeeds in hosting the World Cup, it will be a success for the whole [Middle East] region, which is a conflict zone with its instability – economically, socially and politically,” says Hind Bint Abdul Rahman Al-Muftah, the Gulf state’s ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva, in a rare interview.

“It may generate a new awareness of how this region can be invested in, and send a message that we can be part of how we engage sports in human rights, peace-making and conflict-management,” she adds.

AFP

As Qatar embarked on making the 2022 World Cup bid a reality, reports of abuses and deaths of migrant workers building the infrastructure became a growing liability to the upbeat narrative the gas-rich country was eager to project. WorkersExternal link from impoverished communities in south and east Asia were often denied wages, forbidden from changing jobs, and unable to freely leave the country. Some foreign workers also faced harsh punishment for criticising the system.

A 2021 investigation by The GuardianExternal link newspaper found that at least 6,700 migrant workers died in Qatar between 2010 and 2020, as the country readied itself for the sporting event. However, it is unclear how many of these workers were employed on World Cup construction projects. Qatari authorities say that 37 workers have died while working on tournament building sites, with only three of these deaths resulting from a work accident. For its part, the Geneva-based International Labour Organization (ILO) conducted what it calls an “in-depth analysis”External link of work-related deaths in Qatar and concluded that 50 workers died in 2020, over 500 were seriously injured, and 37,600 suffered mild injuries – and all mainly in the construction industry.

Under pressure in particular from the Geneva-based International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and the ILO, Qatar announced labour reform commitments seven years after winning the bid, including banning midday outdoor work during summer months, allowing workers to leave Qatar without employer permission, and establishing a minimum wage.

But advocacy group Human Rights WatchExternal link said these measures have been “woefully inadequate and poorly enforced”.

Corruption investigations into the bidding process also got under way. In late 2021 the United States Department of Justice saidExternal link a number of FIFA officials had received bribes to vote for Qatar in 2010.

And in France investigations are ongoing into a meeting between former president Nicolas Sarkozy, the former president of the European football federation UEFA, Michel Platini, and the Qatari emir days before the successful bid. The allegation is that economic benefits were obtained in exchange for a French vote. No charges have been filed.

Less than a month before the World Cup kickoff, Tamim Bin Hamad Al-Thani, the emir of Qatar, described the event as a “major humanitarian occasion” in a speech to the Shura council, the legislative body. He condemned criticisms of Qatar as “fabrications”.

Sports has been central to the government’s policy. It was even included in the Qatar 2030 sustainability and development plans as an element that can help the country to diversify its fossil fuel-intensive economy, promote a healthier lifestyle, and attract tourists and foreign residents. Investing in sports is also a way for the authoritarian country to sweeten its international image and build diplomatic ties.

“Qatar is really putting all of its efforts into how to recruit and invest in the sport itself, through ties with FIFA, NGOs and organisations working within the framework of sports, as a language to emphasise basic human rights, peace, action and mediation,” says the ambassador.

swissinfo.ch

Intricate relationships

Over the past decade Qatar has cast a complex web across numerous Geneva-based UN agencies. It has doubled its overall relative weight as a contributorExternal link to the United Nations, known as scales of assessment. Between 2012-2022, this included donations of $49 million (CHF48 million) to the UN refugee agency (UNHCRExternal link) for the purpose of helping refugees and displaced people across the Middle East, Bangladesh and Somalia, according to the UN.

Al-Muftah says an agreement was concluded recently between the UNHCR, Qatari “charitable organisations” and the World Cup hosting committee to build local sports communities in African countries.

Qatar also has its foot in the World Health Organization (WHO) through Gianni Infantino, current president of FIFA and a regular visitor to Geneva. In October 2021, Infantino praised a special partnershipExternal link between the emirate and the WHO to promote a “healthy and safe FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022”.

Before major renovations were to take place at the UN complex known as the Palais des Nations, the emirate left its mark on Geneva. In 2019, a year before Qatar became a member of the Human Rights Council, its foreign minister inaugurated a $22 million make-over of the second-biggest conference hall at the site.

The UN press office in Geneva told SWI swissinfo.ch that a General Assembly resolutionExternal link in April this year, which welcomed Qatar’s hosting of the World Cup as a first in the region, underlined the UN’s “long-held position that sports are an important tool in promoting certain objectives, especially in the areas of development and peace.”

The resolution said the tournament represented a “public health benchmark” for other countries wanting to host sporting events in the future, through “the promotion of physical and mental health and psychosocial well-being”.

Qatar also spearheaded its own initiatives, including the International Centre for Sports Security (ICSS), registered in Geneva, and an ICSS offshoot, the Sports Integrity Global Alliance (SIGA).

Both have served the emirate well in widening its access to international institutions through its claimed role as a supporter of integrity and transparency in sports (see Part 2 and Part 3 of this series). By concluding agreements with various UN agencies and offices, both of these Swiss-based sports organisations have gained recognition and visibility, not least in press releases from parties involved.

Also working with Qatar on its own anti-corruption and integrity agenda has been another organisation, the Rule of Law and Anti-Corruption Centre. ROLACC was inaugurated in Geneva in 2016 by its founder, Ali bin Fetais Al Marri, Qatar’s attorney-general, who was also the UN Special Advocate on the Prevention of Corruption. The unveiling took place in the presence of Michael Møller, former director-general of the UN in Geneva, and Kofi Annan, the late UN secretary-general.

Qatar Attorney General Ali Bin Fetais Al-Marri speaks to reporters in Doha on June 20, 2017

AFP

With Qatar’s backing, ROLACC partnered with the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to award anti-corruption prizes. Qatar, through its emir, donated to the Vienna-based agency a sculpture of a hand reaching upwards that was meant to represent the fight against impunity. Qatar’s UN mission said other ROLACC prizes will be distributed in the emirate during the month of November.

After media reports questioned the source of funds used by Al Marri to purchase expensive properties in Paris and Geneva, including ROLACC’s offices registered under a Swiss company he owned, plus a vast home in Cologny, French newspaper Le Journal du DimancheExternal link reported that Al Marri faced charges in France, including for money laundering. The two cases are ongoing.

During a signing session at the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) in Geneva in early November, Al Marri told SWI swissinfo.ch that “over the past two years of Covid-19” ROLACC has been operating from Qatar. In response to a question about charges against him, he said, “I don’t have any idea. I fight against corruption.”

No mention of human rights

Qatar’s attempt at whitewashing both the human cost of the games and the corruption charges related to the bid does not come without its own controversies. Rights groups have accused the country of pushing a one-sided agenda that airbrushes the country’s human rights abuses.

Jens Sejer Andersen, director of Danish sports transparency initiative Play the Game, who did not want to single out Qatar, takes issue with the use of sports by authoritarian regimes.

“If you look to values that sport claims to represent and promote, sport should stand on the side of democratic values, individual and voluntary association life, team-building and balance and respect of team,” he tells SWI swissinfo.ch. “These values should also not be put in the hands of sinister forces.”

That Qatar is recycling those values to its own benefit through formal and informal channels in Switzerland is worrying to some.

Amnesty International on 17 November 2013 released a report blasting the conditions of migrant construction workers in Qatar, as the country prepares its infrastructure for the 2022 FIFA football World Cup.

Keystone / Amnesty International/handout

“Official Switzerland has been silent as always,” says Pieth. “It is the place where everything happens and where everything is tolerated.”

“[The government] doesn’t care one bit, and doesn’t even realise what is happening,” he adds. “They are being used as a platform.”

A spokesperson for the Swiss mission to the UN in Geneva wrote to SWI swissinfo.ch: “The Swiss government is committed to the respect of human rights in sport in general and in particular also for the FIFA World Cup 2022 in Qatar.” The government “has been committed for more than ten years to improving the working and living conditions of migrant workers in the Middle East, including Qatar, through support to reforms in the Gulf countries via partner organisations and in direct dialogue with the Qatar Ministry of Labour.”

It said that Switzerland did not cooperate with ICSS, SIGA or ROLACC.

More than ten years into Qatar’s public relations push, it is difficult to precisely pinpoint what the emirate has achieved. Within the International Geneva ecosystem, criticism of Qatar’s human rights record may be somewhat blunted, with some organisations shying away from condemning Qatar directly. A global reportExternal link on forced labour published by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in September said “significant progress” has “positively impacted” hundreds of thousands of migrant workers in Qatar after reforms were enacted following negotiations with the UN agency.

Construction workers on top of the roof of Al Janoub stadium during a media tour in Doha, Qatar, 16 December 2019. Al Janoub stadium is the second among the eight stadiums for the FIFA World Cup 2022 in Qatar.

Keystone

Al-Muftah, the Qatari ambassador, defends the timing of the reforms, rejecting claims that the changes were a result of external pressure. “The World Cup was not the main reason behind the labour reforms, but it really accelerated action within the ILO,” says the diplomat.

She insists that the reforms will remain beyond this year’s sporting event. The ILO report went on to add that many workers still do not benefit from these legal changes. Non-payment of wages, retaliation of employers against staff wanting to change jobs, and difficulty in accessing justice continue.

As a current member of the UN Human Rights Council, Qatar hosted a side event during the September session to discuss human rights-related challenges for Least Developed Countries (LDCs), ahead of a conference to be held next year in Doha.

Among the attendees was Rolf Traeger, head of the LDC section at the UNCTAD, the UN office on trade and development. He rejected any contradiction between workers’ rights abuses in Qatar and the government’s international support.

“Qatar is a provider of employment to lots of migrants,” says Traeger. “You can then discuss the conditions [for those workers in the emirate].”

Meanwhile, the UN human rights office told SWI swissinfo.ch that since the last visit from its Special Rapporteur on migrant rights in 2013, Qatar had not responded to requests for a follow-up visit this year. Requests by other UN human rights investigatorsExternal link to visit the country to report on everything from slavery to freedom of religion were either postponed by the state or have gone unanswered.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/gw

This article was amended on November 17 to provide additional information on the number of migrant workers thought to have died in Qatar.